When I’m reading a book and come to a block of description that doesn’t carry the action forwards, I tend to become bored and skim over it at best or skip it all together at worst. For me, descriptions of places should be enough to set the scene and should be written through the observations of the current point-of-view character: not everyone notices the same details or recalls them correctly, as evidenced by eyewitness reports having been shown to be unreliable1. Unreliable or biased narrators can add complexity and depth to the plot.

Don’t pause the action

The biggest problem with a huge block of description is that it stops the action. I never realised this was why I disliked it until it was made explicit by a creative writing teacher. I want to find out how Auntie is going to react to the news she’s just been told, not learn that the wallpaper is a Laura Ashley design from 1987 and that the curtains are a beautiful shade of duck egg blue that co-ordinate wonderfully.

An example comes from my current reading, ‘s A Song of Ice and Fire series:2

A moment later the two champions appeared from opposite sides of the garden. The knight [Ser Vardis Egen] was attended by two young squires, the sellsword [Bronn] by the Eyrie’s master-at-arms.

George R. R. Martin, A Song of Ice and Fire, locations 7318–7335, 5-book box set, Kindle Edition

We’re watching the start of a trial by duel, where Tyrion Lannister is the accused. The excitement is building: a duel! Who will win? What will happen if Tyrion is found guilty?

But then we freeze the action while we examine closely what each of the duellers is wearing:

Ser Vardis Egen was steel from head to heel, encased in heavy plate armor over mail and padded surcoat. Large circular rondels, enameled cream-and-blue in the moon-and-falcon sigil of House Arryn, protected the vulnerable juncture of arm and breast. A skirt of lobstered metal covered him from waist to midthigh, while a solid gorget encircled his throat. Falcon’s wings sprouted from the temples of his helm, and his visor was a pointed metal beak with a narrow slit for vision.

Bronn was so lightly armored he looked almost naked beside the knight. He wore only a shirt of black oiled ringmail over boiled leather, a round steel halfhelm with a noseguard, and a mail coif. High leather boots with steel shinguards gave some protection to his legs, and discs of black iron were sewn into the fingers of his gloves. Yet Catelyn noted that the sellsword stood half a hand taller than his foe, with a longer reach … and Bronn was fifteen years younger, if she was any judge.

ibid.

The point is that Egen is armoured to the teeth, whereas Bronn wears a more lightweight affair, allowing freedom of movement and quickness of foot. But this could so easily have been incorporated into the text of the fight itself, and we wouldn’t have had to stop the action for it. We’d hear Bronn’s sword clanging on Egen’s rondels, perhaps chipping off some of the cream and blue enamel. We’d see Bronn skipping out of the reach of Egen’s handsome double-edged longsword

ibid., location 7344. Imagine if a film freeze-framed or used bullet time3 whenever a new character came on-screen just so we could take in what they were wearing.

The next passage intersperses the description throughout the narrative:

They knelt in the grass beneath the weeping woman, facing each other, with [Tyrion] Lannister between them. The septon removed a faceted crystal sphere from the soft cloth bag at his waist. He lifted it high above his head, and the light shattered. Rainbows danced across the Imp’s face. In a high, solemn, singsong voice, the septon asked the gods to look down and bear witness, to find the truth in this man’s soul, to grant him life and freedom if he was innocent, death if he was guilty. His voice echoed off the surrounding towers.

When the last echo had died away, the septon lowered his crystal and made a hasty departure. Tyrion leaned over and whispered something in Bronn’s ear before the guardsmen led him away. The sellsword rose laughing and brushed a blade of grass from his knee.

ibid., locations 7318–7335

There isn’t a huge amount happening here, but the septon’s actions aren’t being held up so much by the description; rather, the action of the fight is being held up by the septon’s actions; a subtle difference.

Robert Arryn unwittingly hits the nail on the head in the very next paragraph:

Robert Arryn, Lord of the Eyrie and Defender of the Vale, was fidgeting impatiently in his elevated chair.

ibid., locations 7318–7335When are they going to fight?he asked plaintively.

I’m not saying there should be no description whatsoever in a story — on the contrary, it’s needed to set the atmosphere, show the reader what your created world is like, etc. So how should description be written?

Write how Monet painted, not how Constable did

For me, it’s enough to give an impression of how a person appears or what a location is like. My imagination can fill in any gaps that the author leaves. As put it:4

Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s.

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

I’d much rather the author focus on creating an atmosphere of happiness or foreboding or heartbreak or whatever.

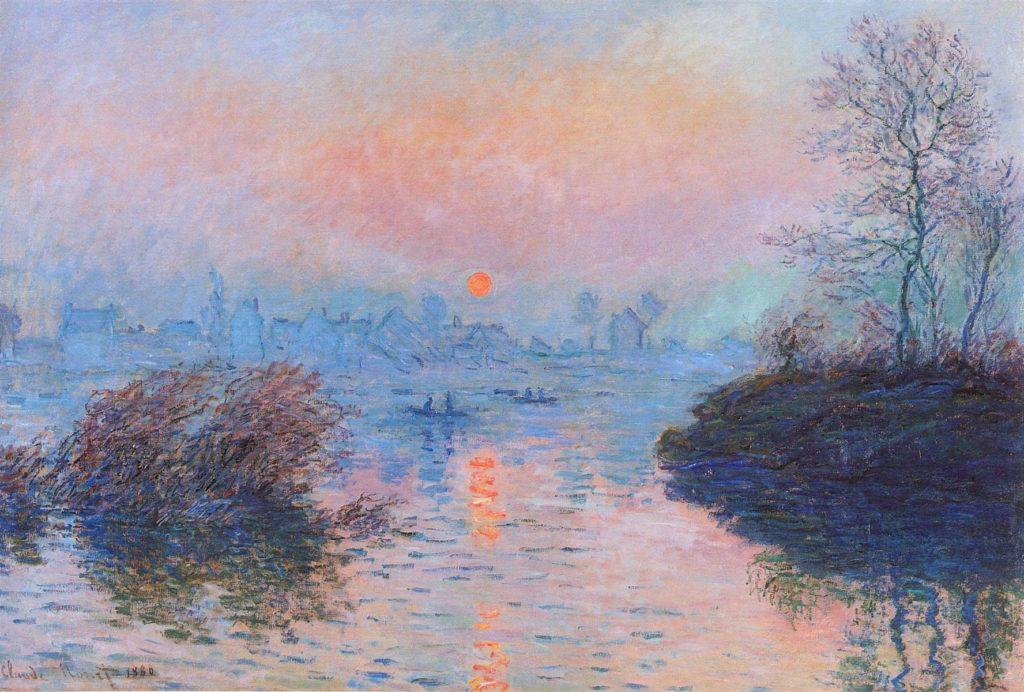

It’s like the difference between a painting by John Constable and one by Claude Monet.

An author who describes too much is like a Constable painting.* For example, look at all the details in his painting of Wivenhoe Park in Essex. It’s a lovely painting, but there are few blanks to be filled in by the viewer’s imagination. Now think about how you’d include all that detail in a story: it would take pages and wouldn’t progress the narrative, unless you were particularly careful to introduce it gradually and through your character’s observations only. One character may not have noticed Wivenhoe House in the background; another may have miscounted the number of cows; another may not have noticed the boat.

Monet gives an impression6 of a scene, without giving all the details. It is up to the viewer to interpret the picture, to fill in the details. Compare the boats in his Sunset on the Seine with the boat in Constable’s Wivenhoe Park. In Constable’s boat, we can see that it is a rowing boat with two people in it. We can see what they’re wearing and what they’re doing. I could go into more detail, but it would be tedious. In Monet’s boats, we see only that there are some boats with two people in each. We are free to imagine they are rowing boats; we are free to imagine what the people are wearing and what they’re doing. Our imaginations have to work to see the whole of Monet’s picture.

If reading is to stimulate the imagination, as said, we must be more like Monet in our writing, and less like Constable, lest we stifle ourselves and our readers. Indeed, Albert Einstein valued imagination more than knowledge:

Imagination is more important than knowledge. For while knowledge defines all we currently know and understand, imagination points to all we might yet discover and create.

Albert Einstein

Describing every last blade of grass allows the reader to know the world you have painstakingly created, but doesn’t allow them to discover it.

* Please note that I’m not saying I dislike Constable’s paintings. I do like them, but that’s not the point here.

References

- 2005. The problem with eyewitnesses at BBC News.

- 1991–. A Song of Ice and Fire series.

- Bullet time at Wikipedia.

- John Constable at Wikipedia.

- Claude Monet at Wikipedia.

- Impressionism at Wikipedia.